The main suppliers of debt with negative yields in recent years have been core euro zone countries and Japan, with Switzerland playing a minor supporting role. Negative rates across the euro zone have become a thing of the past, even on shorter maturity debt, as the European Central Bank belatedly joined in the rush to raise borrowing costs. It is now a much more modest $1.1 trillion, as the financial world returns to something more akin to normality as the Alice-Through-the-Looking-Glass era of getting paid to borrow finally ends.

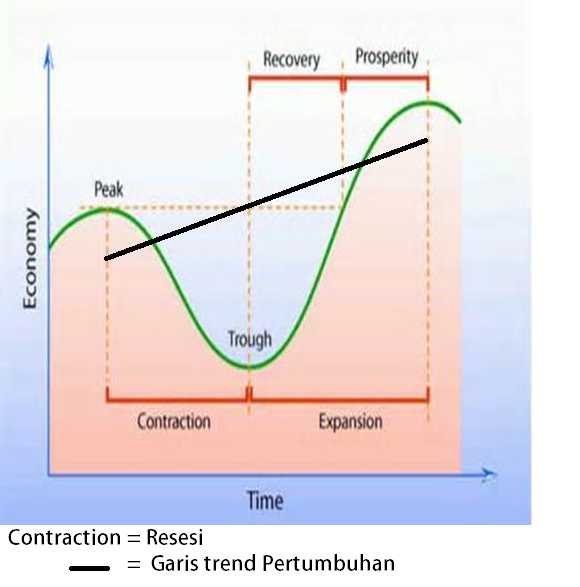

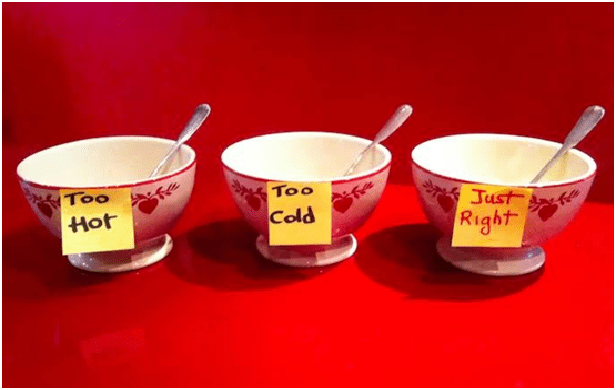

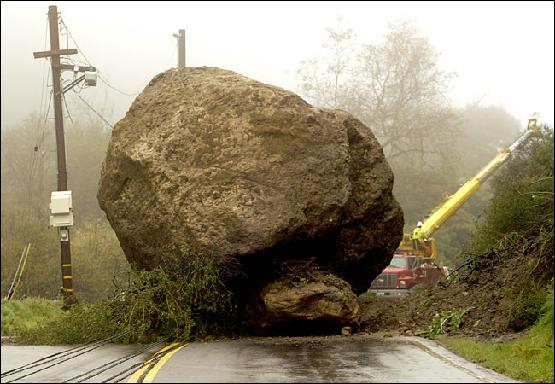

Its zenith in early 2021 saw more than $18 trillion of debt offering sub-zero rates. The universe of negative-yielding bonds has withered as the interest-rate hiking bandwagon picked up speed. Longer term, the growing trend of de-globalization, with increased onshoring of manufacturing facilities in the West, may see reduced trade with Asia. The broader economic picture, though, is also less favourable, with the delayed reopening of China’s economy from lockdowns and the looming threat of recession in many parts of the world. Much of the retracement is down to port delays finally reducing and improved transit times. This offers a welcome logistical respite to supply chains and the accompanying inflation pressure. The cost of moving goods around the world has nearly returned to pre-pandemic levels, having fallen 80 percent from its peak in September 2021. Given that the US central bank effectively dictates how high global interest rates will have to go, the must-watch economic indicator for 2023 will be US labour-market data, specifically on pay. Until this crucial measure comes back under control, the Fed can't stop hiking interest rates. But the number has been running at more than 5 percent for over a year. It is devilishly hard to prevent a self-perpetuating spiral, where increased living costs lead to ever higher-demands for salary improvements.Īverage hourly earnings can, in normal times, comfortably hover a bit above the Federal Reserve's 2 percent inflation target. This is how inflation expectations get embedded into economic behaviour. Overly-hot wage increases keep central bankers awake at night. Stagflation looks like the most likely outcome, at least for the first part of this year. It's getting even trickier as the International Monetary Fund estimates one-third of the world’s economies are either in, or about to fall into, recession. Global inflation had slowed close to 2 percent by the start of 2021. But gargantuan pandemic stimulus programs have combined with an energy shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the logistical nightmare of supply-chain blockages to produce a fivefold increase in consumer prices. While the pace of central bank rate hikes may moderate in the coming months, the mopping-up operation is far from over. The post-pandemic surge in consumer prices has affected all of the world’s economies, encompassing goods and services. That strikes us as unlikely either team transitory wins the day and yields decline, or increased friction in global trade keeps consumer prices and bond yields rising. The consensus forecast among economists surveyed by Bloomberg is for 10-year Treasuries to be at 3.5 percent by the end of 2023, little changed from the current level of about 3.85 percent. US yields, the global benchmark, have blazed the trail towards significantly higher levels. Overly-generous monetary and fiscal stimulus during the pandemic has led to runaway inflation - kryptonite for bonds. Your guess is as bad as ours as to what happens next in fixed income. At current levels, borrowing costs in the debt market are in line with their 20-year average. That multi-decade downtrend has clearly been broken, with the average 10-year yield across G-7 bond markets more than doubling last year from the past decade’s mean of 1.3 percent. Since the 1980's, debt yields have been steadily declining. Too much tightening risks serving up cold economic porridge as growth becomes moribund. Given how badly the guardians of monetary stability misjudged the post-pandemic environment, we’re sceptical of their ability to concoct a Goldilocks economy.

The key for financial markets in the coming year will be whether policy makers can engineer a soft landing for the global economy, or whether recession becomes endemic. Rampant inflation was met by central banks racing to hike official interest rates, trashing returns on almost every asset class with the exceptions of gold and other commodities.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)